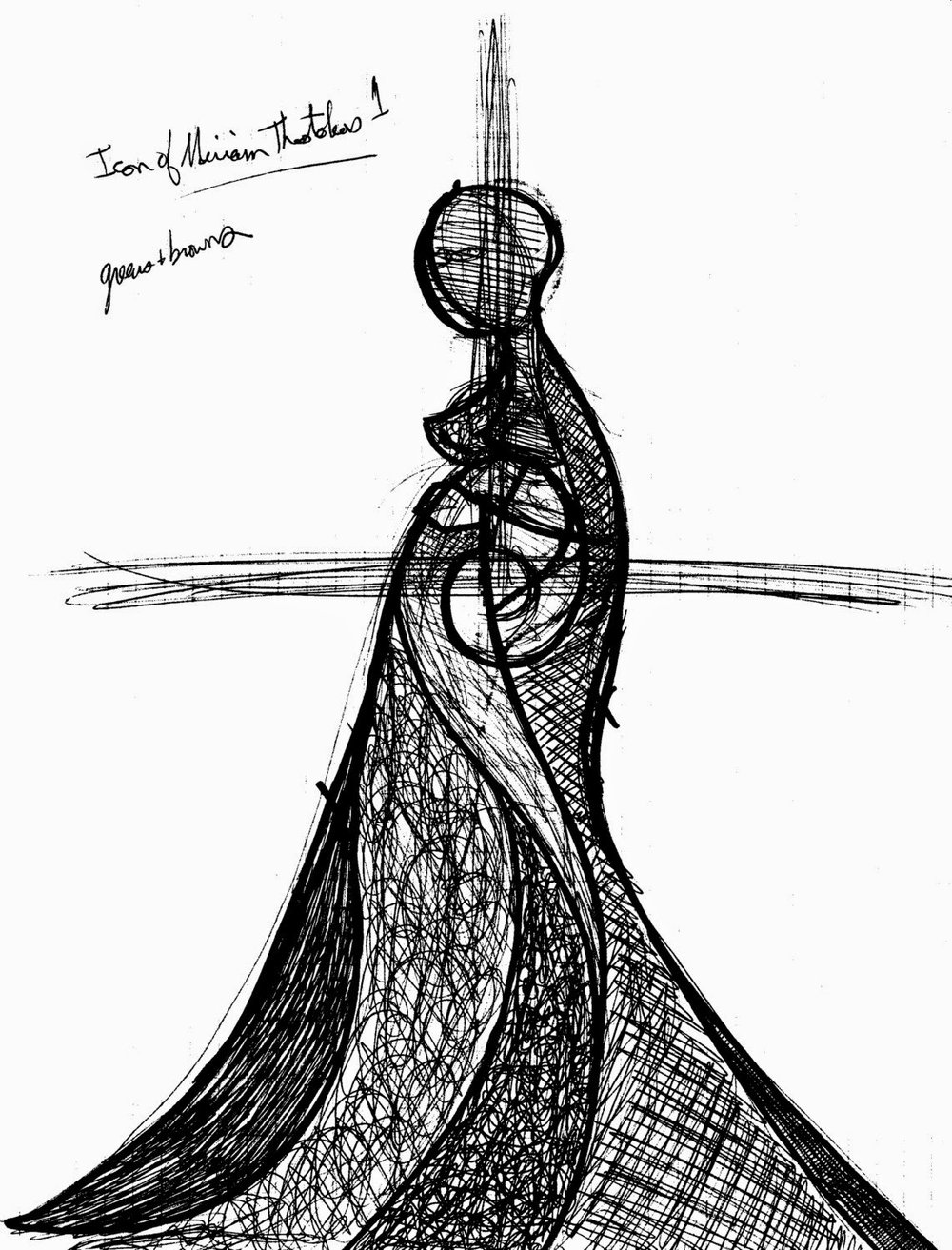

A Mary the mother

of Jesus was a prophet.

Like Isaiah and Micah and Amos and

Habakkuk.

Let’s dig into that for just a

moment.

There in Luke is a great example of

what we call an annunciation form—

basically, there are bits of

scripture

that are very similar to each other,

things like the traditional form of a

pastoral letter,

or love poems, or proverbs,

or the form of announcing a

miraculous birth.

You remember Abraham and Sarah

and their miraculous, late-in-life

birth, right?

Or Hannah mother of the prophet

Samuel?

Their stories, when the angels or God

visit

and tell them of their impending

pregnancy,

generally follow a particular form.

Interestingly, while Mary’s story is

indeed

a birth announcement and fits that

form,

it actually fits a different form

much more closely

—the prophetic call.

Like Moses, Gideon, Isaiah, Jeremiah,

and Ezekiel before her,

Mary encounters an angel

who calls her to some sort of

difficult action,

Mary objects to the call,

she is reassured and given a sign.

B It turns out

lots of early church writers saw this well before I did,

but it’s an image of Mary that we’ve

lost over the years

—somehow we are left with a quiet,

obedient Mother

without the firebrand language of the

Magnificat

she sings immediately afterwards.

She sings about God’s greatness and

mercy

but she also sings this,

“He has shown strength with

his arm;

he has scattered the proud in the

thoughts of their hearts.

He has brought down the powerful from

their thrones,

and lifted up the lowly;

he has filled the hungry with

good things,

and sent the rich away empty.”

It’s reminiscent of the song of Moses

and of basically all of the Hebrew

prophets.

God is indeed great and merciful

AND ALSO is about justice and

significant change to the status quo.

If you’re poor or afflicted, you’re

gonna get fed.

Also, if you’re comfortable or in

power,

you’re gonna get taken down a peg or

two.

Prophets, you see, are a bit

difficult.

They’re not domesticated.

They speak from their own oppressed

group.

They speak the languages of challenge

and hope.

Prophets, Mary included, see clearly

what is,

the patterns of human behavior

and how we consistently screw things

up.

And prophets, Mary included, see what

can be,

the potential for beauty and

compassion and grace.

Prophets, Mary included, speak to

their own oppressed people

and say, “This is terrible but it

won’t last.

If it’s not okay, it’s not the end.”

It’s good news, but it might not seem

like it.

C Pastor Larry and

I used to argue this point.

He’d say, “Good news is always good

news.”

Being contrary, I’d say, “No it’s

not.”

The word “Gospel” literally means

“good news”

and I agree that it is in fact always

good.

BUT it doesn’t always feel like it.

That the rich—spoiler warning, that’s

us

—that the rich will be sent away

empty sounds like a threat.

That the proud—spoiler warning,

that’s also us

—will be scattered sounds like bad

news.

This is the Gospel which says you

lose your life to find it

and that’s damned hard. That’s

miserable. I don’t want that.

The leveling of the playing field

that Mary sings about

and that Isaiah writes about and that

all the prophets

and law-givers and poets of our

scriptures talk about

—that leveling means we might all

lose something

and we will all gain something even

better.

Past that loss of wealth or status or

security,

past

Good Friday, past the pain of pregnancy and childbirth

is the New Thing that God is making.

Mary says to us,

“This is terrible but it won’t last.

If it’s not okay, it’s not the end.”

“When a

person in a marginalized group is voicing their concern over something you’ve

done, it’s a natural reaction to jump and try to defend yourself. Taking the

time to listen and truly understand goes an incredibly long way to promoting

the understanding that is so desperately needed...”[1]

As we continue in this Advent season,

as we wait for something new with

increasing agitation,

when every one of us is pregnant with

possibility,

I invite you to listen to Mary’s

story retold.

D Mary stands in

her home, kneading bread for dinner

and looking absently out the window.

She sees her little son Jesus running

around with the neighbor kids

playing chase and she corrects

herself

—not little son, not any more, was he

ever little,

seemed pretty big when he came out,

where has the time gone.

Mary watches as her son stops to help

up one of the smaller children

who’s fallen in the dust,

then takes off like a shot around the

corner of another house

and the Roman soldier keeping an eye

on their neighborhood.

Mary presses down hard with the heel of her hand into the

dough,

flips it over, presses again,

the repetitive motion part frustration

and part meditation.

Her thoughts drift gently from her

son’s momentary kindness

to his tantrum this morning about

breakfast

to his sleeping face last night

to that same face, softer, rounder,

more covered with snot,

lo, these many years ago.

Mary remembers swaddling her baby boy

in that warm, dirty stable

and weeping with joy and terror at

this new thing

—why didn’t anyone say, I can’t

believe how amazing he is,

Joseph can you even…, how could I

love someone this much.

And she remembers the day of the

angel with the same joy and terror

—how can you be so beautiful and so

frightening,

of course I’m afraid, you want me to

do what,

from…Hashem, but…a baby?

Mary’s hands press down hard into the dough,

flipping it over, pressing it again.

Her hands covered in flour and

callouses ache

as she remembers the early days of

pregnancy

—the painful joints, the exhaustion,

the fluttering in her belly which she

kept thinking was the baby

but which was only gas.

And later when the fluttering took

her breath away

and she grabbed for Joseph’s hand to

feel the tiny elbow pressing up

against her belly.

Once she remembers that elbow coming

up and her pushing it back,

tapping it like a message. And the

elbow tapping back.

She smiles as she flips the dough

over to let it rest

and wipes her hands on the towel at

her waist.

Out of the corner of her eye, she sees Jesus and his friends

run helter-skelter back into sight.

She begins to hum as she takes out a

knife to cut up garlic.

It’s a song she’d all but forgotten,

but in the quiet of a rare moment alone,

she remembers.

“My soul magnifies the Lord,

and my spirit rejoices in God my

savior.”

Ah, yes, she thinks, and sighs aloud.

How that song had welled up in her

that day in cousin Elizabeth’s house.

They were both pregnant,

commiserating about aches and pains

and husbands who were attentive but

in the wrong ways.

They talked of swaddling and

breastfeeding

and the births they’d been present

for.

They talked about how the world

wasn’t good enough for their sons,

hands resting protectively on round

bellies.

They talked about their awe

that they could be making people

within themselves.

They talked about their awe that

Hashem had given them this chance,

that maybe their boys would be the ones to change things.

And Mary began to sing her gratitude.

It was an old tune but the words came

from deep within her,

from the knot of baby growing in her

belly and in her heart.

She sang about her own unworthiness

to be a mother

and how overwhelmingly giddy it made

her.

She sang about Hashem’s attentiveness

to the people with no power

and about Hashem’s power to remake the

world.

She sang about justice and regime

change and transformation.

She sang about her sadness

and she sang about her hope that all

would see the face of Hashem

and know the truth of their sin and

blessedness.

In the end, a breathless silence

and then cousin Elizabeth applauded

and called her Prophetess

and they laughed.

Mary begins chopping the cloves of peeled garlic

piled up like coins in front of her

and hums.

This child will change everything, she sings.

This child has already changed everything.

[1] Jessica Lachenal, “Why the Batgirl #37 controversy is

the conversation we need right now.” www.themarysue.com

12/15/14 6:30pm