Psalm 1, has a lot of meat. It reads:

1 Happy are those who do not follow the advice of

the wicked, or take the path that sinners tread, or sit in the seat of

scoffers;

2 but their delight is in the law of the Lord, and

on his law they meditate day and night.

3 They are like trees planted by streams of water,

which yield their fruit in its season, and their leaves do not wither. In

all that they do, they prosper.

4 The wicked are not so, but are like chaff that

the wind drives away.

5 Therefore the wicked will not stand in the judgment, nor

sinners in the congregation of the righteous;

6 for the Lord watches over the way of the

righteous, but the way of the wicked will perish.

On a first reading, it’s fairly innocuous.

Yes, we’re happier when we’re not

terrible to each other.

We’re more fulfilled and connected to

God

when we participate in what God is

doing.

We are more fruitful when we pay

attention to God’s desire for love.

I’m into it.

And wickedness—or sinfulness,

we often experience as that

rootlessness,

that powerlessness over our

wrongdoing

that the psalm describes as chaff

that the wind blows away.

We get bandied about by our desires.

And we crave justice—“those wicked

people need to be punished,”

maybe even “I’m so wicked I need

punishment.”

We long for a just universe where

good is rewarded and evil punished.

I’m still into it.

Maybe we just end the sermon here?

Maybe not.

There’s a thread in modern theology that says

this psalm and many other bits of

scripture

are about something more concrete.

It’s about the haves and the have

nots.

Certainly those who “have” God, as it

were, and those who don’t.

But also about those who have prosperity

and lots of stuff

and those who do not.

As though those things are entirely

related to whether you have God.

The righteous have much, are blessed,

succeed.

The wicked have little, are

miserable, and fail.

So, it follows from this simple

reading that

those who have little, are miserable,

or fail must be wicked. And those who have much, are blessed, and succeed

are righteous.

No?

Don’t we say God helps those who help

themselves?

Sure, it’s not in the Bible, but it’s

true, right?

And look at statistics: look how

closely crime and poverty line up.

But this reading is from a place of privilege.

Let me complexify this for us.

A number of years ago,

I took my diocese’s required Racism

Awareness workshop.

There was a mix of folks from across

the diocese there.

As a conversation-starter,

we were given an envelope with 26

notecards inside.

On each notecard was a question

and we were asked to put those cards

into two piles:

“this does apply to me” and “this

doesn’t apply to me.”

Let me share with you some of the

statements on the cards.

Maybe you can keep a tally of where

you’d put them:

“I can be pretty sure that if I ask

to talk to the person in charge,

I will be facing a person of my

race.”

“I can turn on the television or open

the front page of the paper

and see people of my race widely-represented.”

“I am rarely asked to speak for all

people of my racial group.”

“I can be sure that my children will

be given curricular materials

that testify to the existence and

contributions of their race.”

“I can worry about racism without

being seen

as self-interested or self-seeking.”

“I can choose blemish cover or

bandages in “flesh” color

and have them more or less match my

skin.”

“Whether I use checks, credit cards,

or cash,

I can count on my skin color not to

work against

the appearance of financial

responsibility.”

“If a traffic cop pulls me over, or

if the IRS audits my tax return,

I can be sure I haven’t been singled

out because of my color.”

Hearing where each person put their

notecards was

—and I cannot put this dramatically

enough—

earth-shaking for me.

I had put 25 of the 26 cards in the

“it does apply to me” pile.

And the white folks around me were

similar.

All of the people of color in the

workshop

had put a majority of the notecards

in the “it doesn’t apply to me” pile.

In this moment, I had a sudden,

intense, clear vision

of the privilege that I enjoy as a white

person.

Just recently I read an article in which the author spoke

of grocery-shopping with her

half-sister at their regular store.

Both of them are of mixed-race, but

the author “passes” for white,

that is, she has more Caucasian

features,

whereas her sister looks clearly

black.

The sisters were in line to check out

with their groceries.

The author was first in line, wrote a

check, was not asked for ID,

and began bagging her groceries

while her sister’s were being

scanned.

The sister then began writing a check

as well

and the cashier immediately asked for

ID

and looked intently, the author says

“suspiciously,”

between the ID and the check.

The author called attention to this

behavior,

asking what she was looking for.

The cashier replied it was policy to

ask for ID.

The author asked why she herself

hadn’t been asked for ID

moments before.

The store manager was called. It

became a bit of an issue.

I’m aware that this is an anecdote,

but one which our black brothers and

sisters

would not find surprising.

What is going on here?

I want to be clear that there are all kinds of privilege,

not just this example of embedded

racism.

In this country there’s the privilege

of being comfortable or even wealthy,

of being male, of being straight, of

being educated.

And being privileged in some way

doesn’t mean things haven’t been hard.

Of course

wealthy people have depression and anxiety

and difficult family situations,

but they know they’re going to eat

for the foreseeable future

and they’re going to be respected.

And of course a poor white family will have significant struggles

just as a poor black family will,

but that poor black family will have

other struggles as well.

And an educated white woman might

enjoy many privileges

in her hometown

but be targeted by rape and death

threats in some online communities

because she is a woman.

Privilege changes and overlaps with

lack-of privilege

—we call this intersectionality.

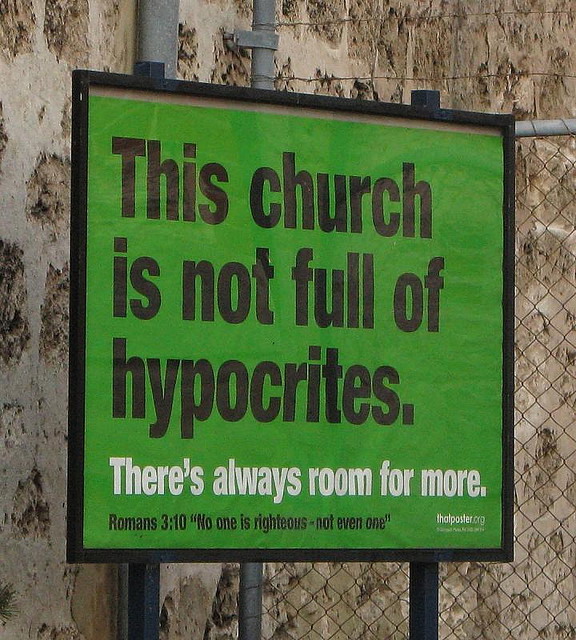

Now, I suspect that by my bringing this up in church,

some folks out there are tensing up.

If it’s because you disagree with me,

I understand, but please hear me out.

I think scripture has something to

speak into our lives here

that’s both difficult and freeing.

If it’s because we don’t talk about

this kind of stuff in church,

I have to ask why not?

Why wouldn’t we talk about the ways

in which

we Christians act like Pharisees,

whether we know it or not?

Why wouldn’t we open our eyes to

systems of oppression

and do what we can to make folks’

lives better?

Isn’t that basically what the

prophets and Jesus were doing?

My point is this:

It is very easy to fall into the

belief that something is not a problem

because it’s not a problem to us

personally.

It’s so difficult to identify with

this idea of privilege

because by its very nature, it’s

invisible if you’ve got it.

And my second point is that

privilege isn’t a bad thing per se,

it’s a question of what we do with it

once we see it.

How do I respond, for example, when I get pulled over for

speeding,

and the officer literally backs away

from me and says

“I can’t give a priest a ticket!”

Rejoice at my good fortune? Insist he

give me a ticket?

Give him a lecture about privilege?

Ask some other officers about policy

and practice and begin dialogue?

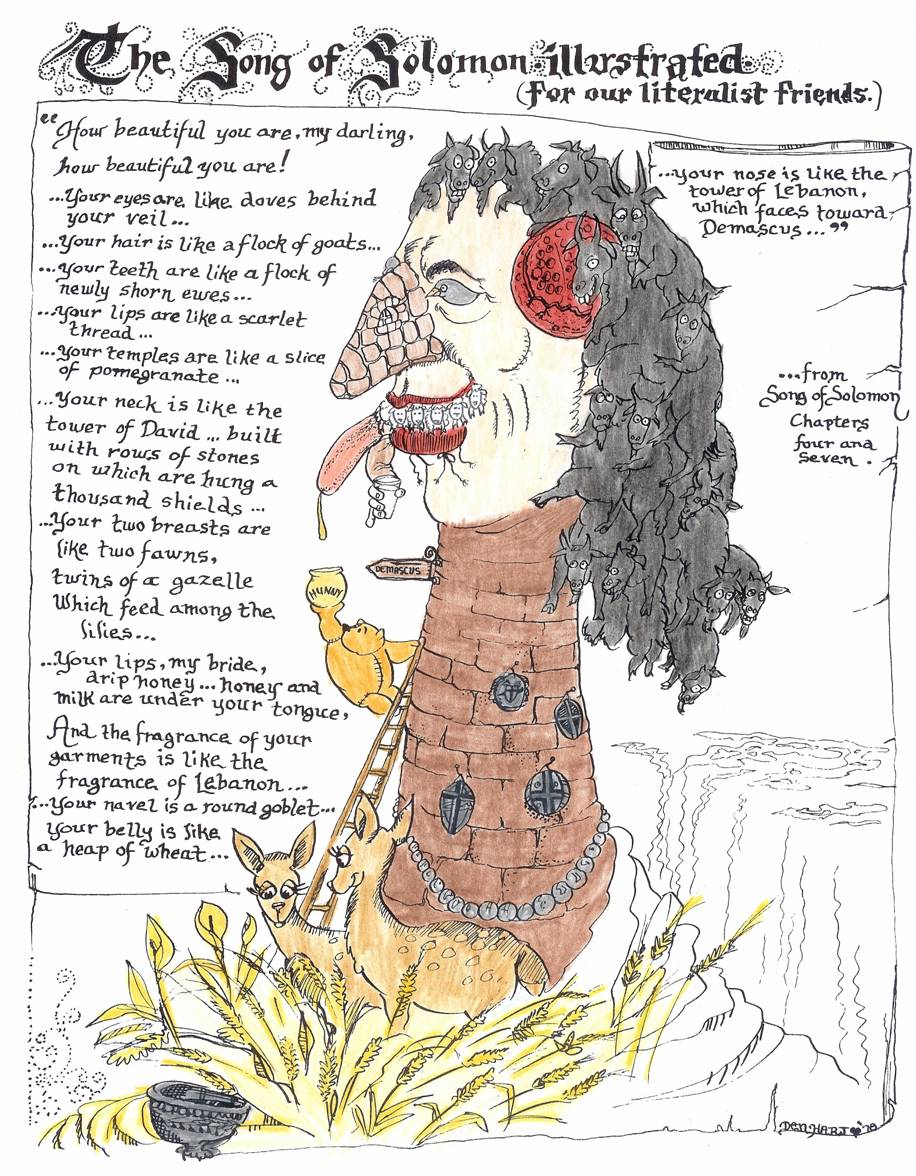

Our scriptures are rife with folks getting away with things

because they’re in charge or favored

or pretty.

And those stories portray privilege

sometimes as violent and terrible

like David’s sending the husband of

the woman he lusted after

to the frontline to be killed.

And sometimes as the only way to save

thousands of lives,

like Esther’s ability to speak to the

king her husband

to spare the lives of the Jews.

And they’re rife with stories of

people on the other side of things,

seeing the imbalance of power,

experiencing the oppression of

invading forces

or economic pressures.

They’re rife with stories of the

outsider and the rejected

pushing back against power and

privilege.

This is Ruth. This is Tamar.

This is Moses in Egypt. This is Mary

Magdalene and Peter.

This is too many people to list.

Looking back at my first description of Psalm 1,

I think we’re being called to

awareness and compassion.

I said, “we are happier when we’re

not terrible to each other.”

Which means we need to notice when

we’re being terrible.

And when someone else is being hurt

by our privilege.

How do we use that awareness to show

that person love?

We are more fulfilled and connected

to God

when we participate in what God is

doing.

Maybe we ask what God is already

doing in our community

rather than plowing forward with what

we know needs to be done?

We are more fruitful when we pay

attention to God’s desire for love.

Not productive, mind you, that’s our consumer

culture speaking.

No, we make the fruit we were meant

to

when we’re paying attention to love

and forgiveness

and understanding and creativity.

How do we educate ourselves about

issues

that don’t affect us personally?

And how do we learn to forgive?

This is where Psalm 1 gives us some beautiful grace.

It doesn’t say that the Lord watches

over the righteous

but the wicked will perish.

It says “the Lord watches over the way of the righteous,

but the way of the wicked will perish.”

The way. The way in which we do

things.

The path we walk. The way of seeing

the world.

God watches over and fosters and

delights

in the path of love that each of us

walks.

I even imagine God,

with one of those brooms they use in

curling,

shuffling backwards in front of us,

sweeping the broom back and forth,

smoothing out the path when it gets

rough…

And God will allow/is allowing the

path of sin and misery

that each of us walks to fall into

disrepair.

Psalm 1 is maybe foreshadowing Psalm

30,

“weeping may linger the night, but

joy comes in the morning.”

In other words, everything will be okay in the end.

If it’s not okay, it’s not the end.

And God invites us to participate in

making things okay.

It will be uncomfortable for us to

face how we are complacent

in the face of suffering.

It will be hard to begin dismantling

our individual and corporate sin.

But we don’t do it alone.

God is walking that path with us,

nudging us towards the one that’s

been cleared,

raising us up when we fall,

and celebrating with us when we

succeed.

This is one message of the cross:

in Jesus’ death and resurrection that

we celebrate this Easter season,

it is not that Jesus reminds an angry

God that we are God’s beloved,

we are reminded that we are created

in God’s image,

that we are God’s beloved, that we

were made for love.

God’s been there all the time,

maintaining the universe,

shining love on all of us.

We just forgot.

On the cross, Jesus showed us

where all our grasping and violence

and moralizing lead us.

And in the empty tomb, Jesus shows us

all the possibilities of creation.

We can be and are like trees planted

by streams of water,

which yield their fruit in its

season,

and their leaves do not wither.

May it be so.